[2023]

[2022]

[2021]

[2020]

[2019]

[2018]

[2017]

[2016]

[2015]

[2014]

[2013]

[2012]

[2011]

[2010]

[2009]

[2008]

[2007]

December

November

October

September

August

July

June

May

April

March

February

January

[2006]

[2005]

[2004]

[2003]

[Wed Sep 26 14:10:58 CEST 2007]

Paul Murphy writes an interesting piece in ZDNet about why the Linux desktop hasn't suceeded yet. It boils down, he argues, to the lack of a true killer app:

Food for thought. {link to this story}The most important reason you don't see Linux desktops everywhere you look is tht Linux desktop applications aren't generally compelling.

[...]

What's going on is that user level decision makets focus on applications, not operating systems. Apache drives Linux adoption because Apache offers world leading technology —a positive reason. In contrast, Linux drives OpenOffice adoption, not because it isn't from Microsoft, or because it doesn't cost anything —all negative reasons; all ultimately based on seeing OpenOffice, or whatever desktop app you care about, as a good enough substitute for the real thing.

And because people always want "the real thing", the bottom line on desktop Linux is simply that followers are always followers, never winners.

[Fri Sep 21 16:28:36 CEST 2007]

Justin James writes A dirge for CPAN in TechRepublic where he clarifies what's so great about the well known repository of Perl modules:

So, the question he asks still remains to be answered: why? Could it be because CPAN started back in the early days of the Internet, when hackers were still "in control", so to speak, and building community —a community where people gave to others for free something other than just opinions— just came naturally? {link to this story}Why is Perl compeltely unique as a once mainstream (and still not obscure) language in having something like CPAN? Sun never gathered mass with Java as a locus for community content for a huge number of reasons, PHP could have/should have been able to reach CPAN status with PECL and PEAR, but it is nowhere close to CPAN in any respect. Microsoft has made a few attempts with GotDotNet (which is currently being dismembered) and more recently CodePlex.

[Fri Sep 21 16:24:15 CEST 2007]

It's very, very sad when a company loses in court a case where it was seeking for the court to uphold its intellectual rights over a pice of code that its own engineers never wrote and has to close shop as a consequence of it because its whole business relied upon the idea of charging others for their rights to use said code. Yes, I'm talking about SCO, of course. {link to this story}

[Thu Sep 20 15:54:59 CEST 2007]

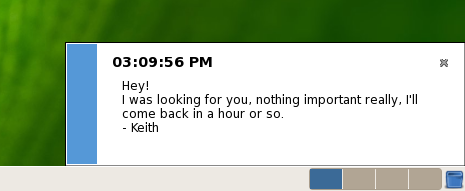

GNOME 2.20 has been released, and it brings a few exciting new goods. For example: the Evolution groupware client has now a new attachment warning to avoid the typical "Sorry, I forgot to attach the file" repeat emails, multimedia applications will now offer to download and install the codecs that may be needed to view a given file (the implementation is actually left to each distribution, which makes its own decision about how to obtain the codecs, but the GNOME folks provide the infrastructure to make it easier to trigger the download and installation of the needed software), the Tomboy note-taking application now makes it possible to use WebDAV or SSH to connect to a remote server and synchronize all the notes that a user has saved... but the new feature that I found most interesting is the one that has been added to the screensaver that makes it possible for people to leave you a note when the screen is locked. All they have to do is click the "Leave Message" button, and the user will see the notes when he or she logs back in. Who said open source developers weren't innovative?

Incidentally, along with all this their documentation website has also been reorganized and redesigned. {link to this story}

[Thu Sep 20 13:17:04 CEST 2007]

APC Magazine publishes a long interview with Con Kolivas that is well worth a read. Mind you, his opinions are quite controversial (check out, for instance, this short piece by Joe Barr in Linux.com), but there is still a good deal to learn from it. He talks about how computing has changed in the last two decades, the specific problems and needs of the Linux desktop users and the overall atmosphere among the kernel developers, among other things. First of all, let's see how he sees the history of computing in the last two decades or so:

Then, on kernel development and his particular contributions:In the late 1980s it was a golden era for computing. There were so many different manufacturers entering the PC market that each offered new and exciting hardware designs, unique operating systems features and enormous choice and competition. Sure, they all shared lots of software and hardware design ideas but for the most part they were developing in competition with each other. It is almost frightening to recall that at that time in Australia the leading personal computer in numbers owned and purchased was the Amiga for a period.

Anyone who lived the era of the first Amiga personal computers will recall how utterly unique an approach they had to computing, and what direction and advance they took the home computer to. Since then there have been many failed attempts at resuscitating that excitement. But this is not about the Amiga, because it ultimately ended up being a failure for other reasons. My point about the Amiga was that radical hardware designs drove development and achieved things that software evolution on existing designs would not take us to.

At that time the IBM personal computer and compatibles were still clunky, expensive, glorified word processing DOS machines. Owners of them always were putting in different graphics and sound cards yearly, upgrading their hardware to try and approach what was built into hardware like the Amiga and the Atari PCs.

Enter the dark era. The hardware driven computer developments failed due to poor marketing, development and a whole host of other problems. This is when the software became king, and instead of competing, all hardware was slowly being designed to yield to the software and operating system design.

We're all aware of what became the defacto operating system standard at the time. As a result there was no market whatsoever for hardware that didn't work within the framework of that operating system. As a defacto operating system did take over, all other operating system markets and competition failed one after the other and the hardware manufacturers found themselves marketing for an ever shrinking range of software rather than the other way around.

However, the desktop PC is crap. it's rubbish. The experience is so bloated and slowed down in all the things that matter to us. We own computers today that were considered supercomputers 10 years ago. 10 years ago we owned supercomputers of 20 years ago... and so on. So why on earth is everything so slow? If they're expontentially faster why does it take longer than ever for our computers to start, for the applications to start and so on? Sure, when they get down to the pure number crunching they're amazing (just encode a video and be amazed). But in everything else they must be unbelievably slower than ever.

Computers of today may be 1,000 times faster than they were a decade ago, yet the things that matter are slower.

The standard argument people give me in response is "but they do such more these days it isn't a fair comparison". Well, they're 10 times slower despite being 1,000 times faster, so they must be doing 10,000 times as many things. Clearly the 10,000 times more things they're doing are all in the wrong place.

{link to this story}What i did was take what was known and try and apply it to the constraints of current hardware designs and the Linux kernel frameworks. While the "global picture" of the problems and solutions have been well known for many years, actually narrowing down on where the acute differences in hardware vs. software have evolved has not. Innovation only lies in the application of those ideas. Academic approaches to solutions tend not to be useful in the real world. On the flip side, pure hackery also tend to be long term disasters even if initially they're a quick fix. Finding the right balance between hackery and not ignoring the many years of academic research is what is needed.

[...]

A flamewar of sorts erupted at the time, because to fix 100% of the problems with the CPU scheduler we had to sacrifice interactivity on some workloads. It wasn't a dramatic loss of interactivity, but it was definitely there. Rather than use

nice to proportion CPU according to where the user told the operating system it should be, the user believed it was the kernel's responsibility to guess. As it turns out, it is the fact that guessing means that no matter how hard and how smart you make the CPU scheduler, it will get it wrong some of the time. The more it tries to guess, the worse will be the corner cases of misbehaving.The option is to throttle the guessing, or not guess at all. The former option means you have a CPU scheduler which is difficut to model, and the behavior is right 95% of the time and ebbs and flows in its metering out of CPU and altency. The latter option means there is no guessing and the behavior is correct 100% of the time... it only gives what you tell it to give. It seemed so absurdly clear to me, given that interactivity mostly was better anyway with the fair approach, yet the maintainers demanded I address this as a problem with the new design. I refused. I insisted that we had to compromise a small amount to gain a heck of a great deal more. A scheduler that was deterministic and predictable and still interactive is a much better option long term than the hack after hack approach we were maintaining.

[...]

If there is any one big problem with kernel development and Linux it is the complete disconnection of the development process from normal users. You know, the ones who constitute 99.9% of the Linux user base.

The Linux kernel mailing list is the way to communicate with the kernel developers. To put it mildly, the Linux kernel mailing list (lkml) is about as scary a communication forum as they come. Most people are absolutely terrified of mailing the list lest they get flamed for their inexperience, an inappropriate bug report, being stupid or whatever. And for the most part they're absolutely right. There is no friendly way to communicate normal users' issues that are kernel related. Yes, of course, the kernel developers are fun loving, happy-go-lucky friendly people. Just look at any interview with Linus and see how he views himself.

I think the kernel developers at large haven't got the faintest idea just how big the problem in userspace are. It is a very small brave minority that are happy to post to lkml, and I keep getting users telling me on IRC, in person, and via my own mailing list, what their problems are. And they've even become fearful of me, even though I've never viewed myself as a real kernel developer.

[Wed Sep 19 12:27:51 CEST 2007]

Red Hat Magazine has a short video with developer Uli Drepper explaining the concept of buffer overflow in very simple terms. Nothing earth-shattering, but it's sort of interesting to see a hacker who is more than capable to explain a concept like this in simple terms. {link to this story}

[Wed Sep 19 11:33:48 CEST 2007]

Well, here is a problem I come across of quite often. I am Spanish, and quite often need to send emails in my native language. On the other hand, since I married an American and have lived in the US for close to 12 years, I am also fluent in English and have friends with whom I correspond in that language. Then, to be honest, when it comes to writing any code whatsover —from shell scripting to Perl, as well as Python, C or even HTML—, I find the US layout to be far more convenient and natural. I ignore if this is because it was precisely English-speaking people who started the whole field of computing or what, but I find that to be the case. So, here I am back in Spain, using an American keyboard, and still need to map certain keys to type the special Spanish characters. Yes, I know, GNOME and other modern desktop environments have a way to configure this through their preference settings, but for whatever reason it does not do the trick for me. In the case of GNOME, it only allows you to configure the so-called compose key, and it gives you a limited set of choices that I truly don't like. Besides, it still doesn't allow me to enter the special exclamation and interrogation marks in Spanish... or at least I haven't been able to figure out how it does it, which at the very least should point to a problem in the way the tool works. In any case, since I finally opted for doing this in a more manual way, I thought it would be a good idea to document here, so perhaps other people can find it when searching around for answers. Here is what I did:

- Use xev to find out the keycode for the dead keys I plan to use (in my case, the window menu, the program menu and the right control keys).

- Create an .xmodmaprc file in my home directory with the following

contents:

! window key keycode 115 = questiondown exclamdown ! right control key keycode 109 = ntilde Ntilde ! right alt key keycode 117 = dead_acute dead_diaeresis

- Either manually run the command

xmodmap .xmodmaprc or add it to your own ~/.xinitrc file (this may change from distro to distro) so it becomes the default configuration. In my case, the next time I logged into GNOME it automatically detected I had the .xmodmaprc file there, and asked me if I wanted to load it as my default configuration. That did the trick.

[Wed Sep 19 10:05:04 CEST 2007]

While reading the latest issue of Red Hat Magazine, I came across a book review of The Practice of System and Network Administration, second edition. I had never heard of this book before, but it certainly sounds as if it could be pretty good from the review written by Christopher Smith:

I also found another glowing review on Help Net Secutiry, written by Mirko Zorz>The Practice of System and Network Administration by authors Limoncelli, Hogan, and Chalup is, simply put, the finest practical guide on the market today covering how to be a good systems administrator. Its charter goal is to provide a framework for solving system problems with an implementation-agnostic, best practice methodology. The book is designed to be easy to both skim around and navigate to the parts that most interest you as well as flowing together well enough to read chapter to chapter.

All in all, it sounds like a really good book on the topic. The authors also publish a blog called Everything Sysadmin with pointers to articles and commentaries on the topic, although the top entries right now are dedicated to the different reviews of the just published second edition of their book. {link to this story}When it comes to work that system administrators are doing the most, this book deals with topics such as data integrity, network devices, debugging, customer care, server upgrades, service monitoring, various services, and basically everything else you may need. Since there are more than 1000 pages, it's unpractical to list all the chapters and provide an overview of each so I'll give you some highlights.

[...]

The attention to detail is evident as is the diversity of data presented in every chapter. For example, when discussing an important topic such as backup, the authors don't just emphasize its importance and recommend solutions, they also discuss time and capacity planning, high-availability databases and offer some insight into possible technology changs.

Readers interested in security will enjoy the chapter dedicated to security policy where the authors cover different organizational profiles and even get into management territory by illustrating some organizational issues as well as the importance of a relationship with the legal department.

What I found to be really valuable in this book besides the technical and organization components, are the details related to how an administrator should behave with customers and present his work in order to be valued accordingly. In the past system administrators may have been perceived solely as technical staff but nowadays they have to work with management on many occasions and their presentation skills are quite important.

[Thu Sep 13 11:15:44 CEST 2007]

According to the old saying, politics makes some very strange bedfellows. Well, so does business. Sun has announced that it will install Windows on its 64-bit servers within 90 days. Scott McNealy's jabs at the Redmond giant are now long forgotten. The more I read about the world of business, the more it reminds me of the world of politics. There is plenty of posturing and rhetoric but, when it comes down to what it truly matters, money and power are all they care about respectively. Not that I think it should be otherwise, but it is something to bear in mind next time we hear the next speech choke-full of grandiose rhetoric... be it from a President or from a CEO. {link to this story}

[Tue Sep 11 10:45:18 CEST 2007]

Remember the old Eudora email client? I bet you do, if you have been on the Internet long enough. Like the Netscape browser, it pushed the envelope a bit further in the mid-1990s, contributing to make things like the Web and email popular among regular people. In that sense, today's Web owes a lot to those two products. Well, as it turned out —and just like Netscape itself— other products ended up smashing it to smithreens and it closed shop —Qualcomm, its owner, finally quit selling the product at the end of May. However, today I read in eWeek that Eudora has been reborn as an open source product after Qualcomm donated its code to the community. It has joined the Mozilla project under the Penelope codename, and its developers maintain that they intend to put together a solution that is based on Mozilla and Thunderbird to complement them, not to compete against them. I am not sure what that means but they already have a beta version available on their releases page. {link to this story}

[Wed Sep 5 19:45:51 CEST 2007]

Theo de Raadt brought up an interesting discussion regarding the legal implications of using dual license (BSD and GPL in this case) for a particular piece of software. As it tends to be the case with de Raadt, he does not stand out for his diplomatic skills, but that does not subtract (or it should not subtract) from the merit of the issue being raised.

It is illegal to modify a license unless you are the owner/author, because it is a legal document. If there are multiple owners/authors, they must all agree. A person who receives the file under two licenses can use the file in either way.... but if they distribute the file (modified or unmodified!), they must distribute it with the existing license intact, because the licenses we all use have statements which say that the license may not be removed.

It may seem that the licenses let one _distribute_ it under either license, but this interpretation is false —it is still illegal to break up, cut up, or modify someone else's legal document, and, it cannot be replaced by another license because it may not be removed. Hence, a dual licensed file remains dual licensed, every time it is distributed.

It all sounds like your usual legalesse up to this point. But, of course, de Raadt being de Raadt, there had to be a controversy which he describes without avoiding the sharp edge:

As I said, it is indeed an interesting issue that de Raadt is bring up here. {link to this story}GPL fans said the great problem we would face is that companies would take our BSD code, modify it, and not give back. Nope —the great problem we face is that people would wrap the GPL around our code, and lock us out in the same way that these supposed companies would lock us out. Just like the Linux community, we have many companies giving us code back, all the time. But once the code is GPL'd, we cannot get it back.

Ironic.

I hope some people in the GPL community will give that some thought. Your license may benefit you, but you could lose friends you need. The GPL users have an opportunity to "develop community", to keep an ethic of sharing alive.

If the Linux developers wrap GPL's around things we worked very hard on, it will definately [sic] not be viewed as community development, and one that has generated its good share of debate. Just take the link at the top of this entry as a starting point.

[Wed Sep 5 08:42:32 CEST 2007]

What does Apple have that it generates so much expectation everywhere? The Spanish press is wondering what Steve Jobs will introduce tomorrow in London, and there are plenty of rumors, enough to fill pages and pages: an iCar commercialized together with German automaker Volkswagen, a new generation iPod nano... {link to this story}

[Mon Sep 3 10:59:20 CEST 2007]

Just came across a new UNIX/Linux timeline that looks pretty cool (here is the direc link to the actual chart). It includes the usual suspects: UNIX System V, BSD, Linux, Mach, etc. By the way, the same document includes a link to a very nice Linux distribution map that is now more needed than ever with so many Linux flavors out there.

Incidentally, while talking about interesting findings, I read in an interview with Ubuntu's Mark Shuttleworth about Gobby (check an article from Debian Package of the Day here), a collaborative editor that allows several people to work on the writing of a given document and discuss it online. {link to this story}