[2023]

[2022]

[2021]

[2020]

[2019]

[2018]

[2017]

[2016]

[2015]

[2014]

[2013]

[2012]

[2011]

[2010]

[2009]

[2008]

[2007]

December

November

October

September

August

July

June

May

April

March

February

January

[2006]

[2005]

[2004]

[2003]

[Tue Aug 28 10:44:08 CEST 2007]

Yesterday, I wrote about Sun changing its stock ticker from SUNW to JAVA. Well, today I come across a piece written by Russell Beattie arguing that Java badly needs an overhaul that offers a different type of argument against Sun's decision:

Beattie goes on to argue his point, centered on two main defects he finds in Java: 1) it is bloated and performs pretty bad (no surprises there!), and 2) the standard Java Class Libraries are too obtuse and limited for everyday use. The piece is quite damning. {link to this story}I like Jonathan Schwartz a lot, but I think that unless some drastic changes are made to Java, the move to JAVA as Sun's ticker symbol is going to be as relevant as changing it to COBOL. I'm using Java less and less as time goes by, not more —the heyday of the language and platform has come and gone, and IMHO, it's going to continue to fade from relevance with increasing speed.

[...]As a user, Flash has supplanted Java in the browser, we've all seen that happen. On my Linux box, I use several C# applications and none that use the JVM (I used to use Azureus, but lately it's been freaking out and crashing (!!) so I gave up on it). On my server I only use a LAMP stack and would never consider a Java server-side app (like for my blog or Jabber server) —I just don't want to waste my server's resources on a bloated JVM.

As a developer, nowadays I would never consider Java for anything besides a very focused set of server processes to which it was well suited. The pain of dealing with Java, and the time/effort it takes to develop using it just isn't worth it to me. Yes, at one point Java was definitely a god-send. It rescued me from the Microsoft hell I was dealing with at the time (this is back in 1999) and opened up a whole new world of options, as well as lead me to Unix, etc. But many years have passed since then, and sadly Java hasn't progressed, and instead has become more and more obtuse and bloated with each passing year. At one point I thought I hated programming because I was just so sick of it... It turns out I don't hate programming, I just hate programming in Java.

In fact, I'd say that many of today's current hot trends in programming are a direct result of a backlash *against* everything that Java has come to represent: lengthy code and slow development being the first and foremost on the list. In Java you generally need hundreds of lines of code to do what modern scripting languages do in dozens (or less). The general up tick in interest in Ruby, Python and PHP during the 2000s all has its roots in programmers who had to work on one Java project too many, and were desperate to find something more efficient and less painful to use. You all know the story —less XML and cleaner, leaner code— and once you've experienced it, believe me, you won't go back.

[Mon Aug 27 11:16:17 CEST 2007]

Jonathan Schwartz recently announced on his blog that Sun would be changing its ticker symbol from SUNW to JAVA, which surprised quite a few people in the industry. His reasons appear to be well grounded though (both Java and Open Office have far more brand recognition these days than good old Sun, and brand recognition does matter in today's world), and the change does not seem to be linked to any major shift in their strategy either:

However, as it has been reported somewhere else, not everybody agrees with the decision. The criticisms go from those who argue that not everything associated to Java is positive —emphasizing the slow performance traditionally linked to the programming language in many people's minds— to the ones who see it as a textbook case of misplaced priorities. {link to this story}... Granted, lots of folks on Wall Street know SUNW, given its status as among the most highly traded stocks in the world (the SUNW symbol shows up daily in the listings of most highly traded securities).

But SUNW represents the past, and it's not without a nostalgic nod that we've decided to look ahead.

JAVA is a technology whose value is near infinite to the internet, and a brand that's inseparably a part of Sun (and our profitability). And so next week, we're going to embrace that realityt by changing our trading symbol, from SUNW to JAVA. This is a big change for us, capitalizing on the extraordinary affinity our teams have invested to build, introducing Sun to new investors, developers and consumers. Most know Java, few know Sun —we can bring the two one step closer.

To be very clear, this isn't about changing the company name or focus —we are Sun, we are a systems company, and we will always be a derivative of the students that created us, Stanford University Network is here to stay. But we are no longer simply a workstation company, nor a company whose products can be limited by one category —and Java does a better job of capturing exactly that sentiment than any other four letter symbol. Java means limitless opportunity —for our software, systems, storage, service and microelectronics businesses. And for the open source communities we shepherd. What a perfect ticker.

[Thu Aug 23 11:36:06 CEST 2007]

There are open source fans who take things way too far, at least in my view. I just came across an article written by Larry Dignan of ZDNet titled Is Google Becoming An Enemy of Open Source? where he blasts Google for not releasing their own core technology (the Google File System and MapReduce, basically) as open source. It happened to Red Hat before, and it is happening to Google now, and I think it is unfair in both cases. These companies have given a lot to the open source community, and continue giving, and it does not strike me as very clever to bite the hand that feeds you, especially when there are plenty of companies out there that take a lot from the open source community and give very little. I do not think it is fair to demand that Google surrenders its core technolgy, the main component that makes it competitive and guarantees its own survival, especially when, as Dignan himself acknowledges, they have already made public enough information in specialized forums that make it even possible for other people to build an open solution that meets the same requirements (Hadoop, apparently, is doing precisely that, and Yahoo! is financing it. One can be a believer in open source (I sure am) and still feel that demanding that companies such as Google, Sun, Microsoft and many others release everything they own as open source is not a tenable position. I sure would like to see it happening, but I have no right whatsoever to make any demands. {link to this story}

[Thu Aug 23 10:24:22 CEST 2007]

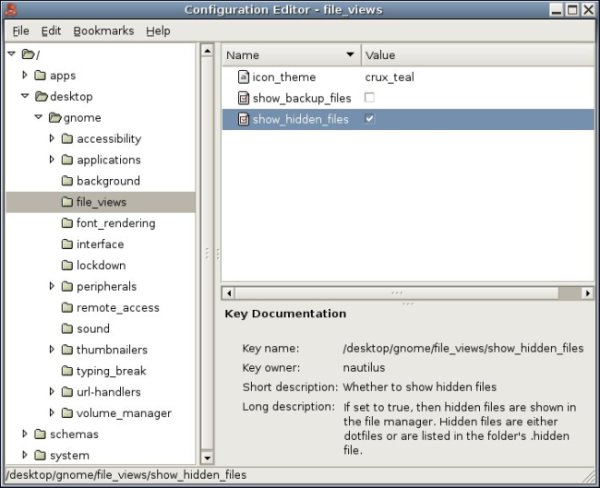

I finally took the time to research how to get rid of a default option in GNOME that bothers me quite a bit: when going through the file selection widget to open a file, it does not show the hidden files by default, therefore forcing one to right-click and check the Show Hidden Files box. Well, the solution is to launch the GConf Editor and go down the following menu:

desktop --> gnome --> file_views: show_hidden_files

Here is a screenshot:

{link to this story}

[Wed Aug 22 12:18:03 CEST 2007]

Reading a very good document on Compiz Fusion —it includes not only a nice summary of its features with short videos to illustrate them, but also a lot of links to resources on how to install it and configure it—, I came across another short piece on Virtue Desktops, the application that introduces the concept of virtual desktops to Apple's MacOS X. It was about time!

By the way, I must point out that the above mentioned article on Compiz Fusion talks over and over again about the "increased productivity" brought about by the product. Let me write this again. I still have to understand exactly what productivity is gained by using a 3D desktop environment, at least until a killer app is discovered. What are the "productivity gains" the author is talking about, after all? The ability to switch between different virtual desktops? Don't I already have that with the traditional virtual desktops approach? The ability to move drag and drop applications from one desktop to another? The same applies here. The ability to have all the open windows show on the desktop at once and pick one of them? Isn't that what Komposé, Expocity and other similar applications accomplish? Sure, it is impressive and it looks good, but leaving that aside I just cannot find any compelling reason to run it solely based on producitivity. As usual, if one hears the same lie repeated a thousand times, it ends up becoming true... or at least lots of people believe it to be true! {link to this story}

[Fri Aug 17 16:35:41 CEST 2007]

eWeek published a short interview with the IT director for the San Francisco Chronicle about running large commercial websites on free Linux that deserves some attention:

In other words, what we already knew but the press usually ignores because it prefers to play to the vendors' hype: many sites out there may still be running on pretty old hardware *and* software (both). Hey, as long as it does what it is supposed to do... Unless one wants to be surprised in the middle of the night, running stable but solid and proven software (and even hardware) does not sound like such a bad thing. {link to this story}— Is it safe for large commercial Web site to run its servers on a Red Hat clone instead of the real thing?

— I think so. We're currently running some trials to find out. We have several dozen servers running Apache on Red Hat 7.3, which is an older version of Red Hat that we are using without a support contract. We have a smaller number of database servers running MySQL on Red Hat Enterprise Linux 3 (RHEL 3), for which we maintain support contract with Red Hat. Recently, however, I've made a policy decision to move our servres to more recent versions of Linux, perhaps RHEL 4 or RHEL5 or equiv alent. When we saw what it would cost us to do that with Red Hat, we decided to look at less expensive options, in particular CentOS, which is a free binary clone of Red Hat compiled from the publicly available Red Hat source code.

[...]

— Does moving to CentOS mean you will drop all your Red hat support contracts?

— No. We plan to keep some of our servers under Red Hat maintenance, just to stay up to date with what they're doing.

[...]

— As the manager of a large commercial Web site serving millions of impressions per day, what keeps you awake at night?

— Well, it isn't my Web servers or my database servers. It's the Network Appliance filers and the Foundry Networks load balancers. If one of them ever failed in a non-recoverable way, our site would go down for a significant period of time. It's never happened so far. We do have good support contracts with these vendors for that. For example, we have a four-hour onsite replacemente policy with Network Appliance. But just the thought that it might happen one day does keep me awake at night sometimes.

[...]

— How often does a large commercial Web site need to replace its servers in order to maintain good availability levels?

— We serve 60 million HTTP requests per day and our site is an important source of advertising revenue, but you may be surprised to know that most of our 35 Web servers are five years old. Although we are gradually adding more modern hardware, most of these older servers continue to work quite well. The new servers are dual processor machines based on dual core Intel Xeons and are obviously far more powerful. But after upgrading to a more recent version of Linux we plan to keep most of the older single processor servers online, except for a few troublesome machines that we will recycle into other areas of our organization.

[Fri Aug 17 13:07:20 CEST 2007]

Just came across a funny article titled What does your favorite text editor say about

you?. The entry for

Well, I do useYou are a minimalist at heart, but you value raw power of a sophisticated, and yet simple editor. You hate to waste key strokes. You laugh derisively at the fools fighting with their silly Notepad like editors. You either use a traditional unix keyboard or you switched around Ctrl and Caps Lock so that they are in their proper places. Chances are that you might be (or have been) a sysadmin. You think that Emacs is not a text editor, but a fucking operating system with a bult in kitchen sink, and a circus tent. You might as well use an IDE.

Sorry, I have received way too many plain text documents over the years that could have been written with a simple text editor and came instead as an MS Word attachment that could potentially be loaded with viruses. Besides, why bother to use Word to put together a simple text document that could just be included in the regular body of the email? I suppose that a rampant level of computer iliteracy can be the only answer. {link to this story}Microsoft Word is not a text editor. You should not be allowed near a computer. In fact you are the cancer that is killing the internet. Kill yourself.

[Tue Aug 14 15:41:58 CEST 2007]

If you run Linux on your desktop and experience any problems configuring your printer (in spite of CUPS), you may be in luck as long as there is an HP produt on the other end. I have read some good things about HPLIP which, according to their SourceForge page, "is an HP developed solution for printing, scanning, and faxing with HP Inkjet and laser based printers in Linux". {link to this story}

[Mon Aug 13 13:12:18 CEST 2007]

Computer World publishes a short interview with Linus Torvalds. If there is something that stands out in the creator of Linux is precisely his humanity, something that would most likely surprise all those who consider techies to be completely devoid of feelings and moral convictions. Check out, for example, this answer:

This guy is definitely made of a different material than the rest of us! {link to this story}— Lots of researches made millions with new computer technologies, but you preferred to keep developing Linux. Don't you feel you missed the chance of a lifetime by not creating a proprietary Linux?

— No, really. First off, I'm actually perfectly well off. I live in a good-sized house, with a nice yard, with deer occasionally showing up and eating the roses (my wife likes the roses more, I like the deer more, so we don't really mind). I've got three kids, and I know I can pay for their education. What more do I need?

The thing is, being a good programmer actually pays pretty well; being acknowledged as being world-class pays even better. I simply didn't need to start a commercial company. And it's just about the least interesting thing I can even imagine. I absolutely hate paperwork. I couldn't take care of employees if I tried. A company that I started would never have succeeded —it's simply not what I'm interested in! So instead, I have a very good life, doing something that I think actually matters for people, not just me. And that makes me feel good.

So I think I would have missed the opportunity of my lifetime if I had not made Linux widely available. If I had tried to make it commercial, it would never have worked as well, it would never have been as relevant, and I'd probably be stressed out. So I'm really happy with my choices in life. I do what I care about, and feel like I'm making a difference.

[Mon Aug 13 11:13:46 CEST 2007]

Linux.com has published a very interesting piece on free and open source software and its philosophical implications. It is actually a quick overview of the proceeds of North American Computers and Philosophy (NA-ACP) Conference that took place in Chicago at the end of July.

It would be interesting to see more multi-disciplinary approaches to the world of technogy. Computing is just too central to our contemporary lifestyle to leave it only to the "experts". {link to this story}Sessions began on Thursday afternoon, with IA-ACP president Luciano Floridi giving the opening address. Immediately following this was a series of four excellent presentations devoted to ethical isues in FOSS [Free and Open Source Software]. In many ways, this panel set the tone for the remainder of the conference.

For example, Samir Chopra and Scott Dexter, one a philosopher, the other a computer scientist, presented a paper on the so-called "Freedom-Zero Problem" with the Free Software Definition: How can one claim that it is morally responsible to mandate the unrestricted access to and use of code even in cases where this will certainly lead to harm? For example, why doesn't the GPL forbid Free Software from being used in nuclear weaponry, or for torturing other humans? This ethically charged issue reappeared in numerous conversations throughout the conference.

In the sessions that followed, topics were more varied. Panels were organized around such areas as ethics in software development, epistemology and Wikipedia, online scholarly resources, and the effectiveness of online education. The level of detail of the presentations varied widely. While one paper might be devoted to high-level introductory material, another would take a close look at a particular perplexing issue. One of my favorites was Jesse Hughe's presentation, entitle "Is Software Malfunction an Oxymoron?", in which he points out how difficult it is to describe what a software malfunction is.

[...]

Saturday morning, Peter Suber delivered his keynote. In a well-structured presentation, he explained the Open Access movement in the scholarly publising world, and presented a sketch of a philosophical argument in support of OA journals and repositories. Conference organizer Tony Beavers said, "Peter Suber's arguments on open access publication were so thorough that it was difficult to think up a counter-argument, even while trying to play the role of devil's advocate".

The main idea driving the OA movement, boradly speaking, is that journal articles, one of the few gengres of non-royalties literature, ought to be provided online free of charge. In many of the sciences and humanities, cutting-edge research is published in topic-specific scholarly journals. But the authors of sch articles are rarely paid, nor are those who act as peer reviewers. Further, authors often give up copyrights altogether. "Authors in this field are not motivated by monetary incentives, but by concerns about prestige and furthering research in the field", Suber argues. Scholars, he suggests, ought to publish their articles with OA journals, and archive copies of these papers with OA repositories. Authour would benefit from greater exposure, while other scholars would benefit from easier access to cutting-edge research.

[Wed Aug 1 17:25:13 CEST 2007]

Remember the dot-com craze? Well, there are plenty of people out there who think that we may be going through something similar now with the Second Life phenomenon. Need an example? Just check out Frank Rose's How Madison Avenue Is Wasting Millions on a Deserted Second Life, recently published by none other than Wired, which can hardly be accused of having an anti-technological slant. So, what is the complaint? Second Life does not have nearly as many users as it claims, we are told. Businesses who decided to build a storefront in the virtual world are not making any money and there are barely any visitors to be seen. Sure, all that is true. Additionally, the interface is quite clunky, as Rose explains in his piece:

And yet, who doesn't remember how clunky navigating the Web was back in 1995? There were also plenty of people back then who didn't believe it would ever be possible to make money out of this crazy idea called the World Wide Web. That was just kids' passtime. The real world with its real money was somewhere else, of course. I just wonder how many of those lost their jobs to companies like Amazon. Yes, the Web did have to go through some growing pains, and I'd expect the same thing to happen to virtual worlds but there is little doubt in my mind that, sooner or later, in one form of another, under the brand name of Second Life of whichever other company that replaces it, this idea will work out in the end. Listen, it just makes sense. Everyone likes the idea of navigating through a virtual world in three dimensions that allows us to recreate our own world and, more important, to imagine a completely different one. So, could the physics engine be improved? Yes. Could the world become more scalable? Yep. It will happen, sooner or later. Just let things run their natural course. You'll see. Chances are that all that and far more will happen, peraps even including new and innovative interfaces that will allow for a more realistic inmersion in the virtual world. {link to this story}One of the things you never see in Second Life is a genuine crowd —largely because the technology makes it impossible. In Stephenson'sMetaverse, corporations established their presence along a bustling, almost infinite long street that residents could cruise at will. Second Life is different. Created by an underfunded startup using a physics engine that's now years out of date, Second Life is made up of thouosands of disconnected "regions" (read: processors), most of which remain invisible unless you explictly search for them by name. Residents can reach these places only by teleporting into the void. And even the popular islands are never crowded, because each processor on Linden Lab's servers can handle a maximum of only 70 avatars at a time; more than that and the service slows to a crawl, some avatars disappear, or the island simply vanishes. "It's really the software's fault", says Andrew Meadows, Linde Lab's senior developer. "Way back when, we used to say. "This is not going to scale".