[2023]

[2022]

[2021]

[2020]

[2019]

[2018]

[2017]

[2016]

[2015]

[2014]

[2013]

[2012]

[2011]

[2010]

December

November

October

September

August

July

June

May

April

March

February

January

[2009]

[2008]

[2007]

[2006]

[2005]

[2004]

[2003]

[Fri Mar 26 12:23:48 CET 2010]

Mac Slocum writes an article on O'Reilly Radar about the web-TV convergence that is worth reading. After commenting how several companies (Yahoo and Google, among others) are working on some sort of convergence of the web and television, Slocum goes on to tell us about new data from Nielsen that suggests that these projects may be headed in the wrong direction. There are several obstacles that make a web-TV convergence quite difficult: while the web is inherently a pull technology, television has always been passive in nature; the two experiences are significantly different by design; and, finally, whichever way you come up with to allow input into a TV set feels quite clunky. Don't get me wrong, convergence is indeed happening, but perhaps not in the way companies think. For instance, the above mentioned Nielsen report clearly states that in the last quarter of 2009 Americans dedicated about three and a half hours a month to simultaneous use of the Internet and television. The practice is becoming more and more widespread. While I don't like it much, I do see my wife doing both at the same time fairly often. The same report also mentions an even more interesting trend:

Slocum's closing commens are also well worth some consideration, I think:The research shows that Americans watch network programs online when they miss an episode or when a TV is not availanle. Online video is used essentially like DVR and not typically a replacement for watching TV.

I wonder what the consequences of all this may be for TiVo and similar companies. {link to this story}...it matters if content is consumed, not how it's consumed. All kinds of effort has gone into bridging the web and TV worlds through brute force. Yet, the most successful cross-media efforts are the ones that let consumers interact through the tools they already use. What makes more sense: integrating Twitter into a television's hardware or helping users tweet during the show?

[Fri Mar 26 12:10:48 CET 2010]

A friend passed a link to this short video where Larry Page, co-founder of Google, lays out what he calls Page's Law, or why your computer runs like crap after 18 months:

He's absolutely right. One more issue to fix in today's software. {link to this story}

[Thu Mar 25 12:39:51 CET 2010]

We learned a few days ago that Google made a decision to stop censoring its results in China. As it could also be expected, the Chinese Government refuses to back down and let its citizens free access to information through the world's most popular search engine. Whatever ends up happening, one has to admire Google's efforts not to do evil, as they always promised in their company motto. Most large corporations don't think twice before grabbing the money, whichever the source. In this case, Google appears to be trying to do the right thing, even if it may cost them in the long run. As I said, whichever way this ends, one has to acknowledge that much. Even if they have to give up and let the Chinese authorities impose whatever restrictions they want, since there is a good chance other companies will just step into the vacuum and try to benefit from it. {link to this story}

[Thu Mar 18 12:47:34 CET 2010]

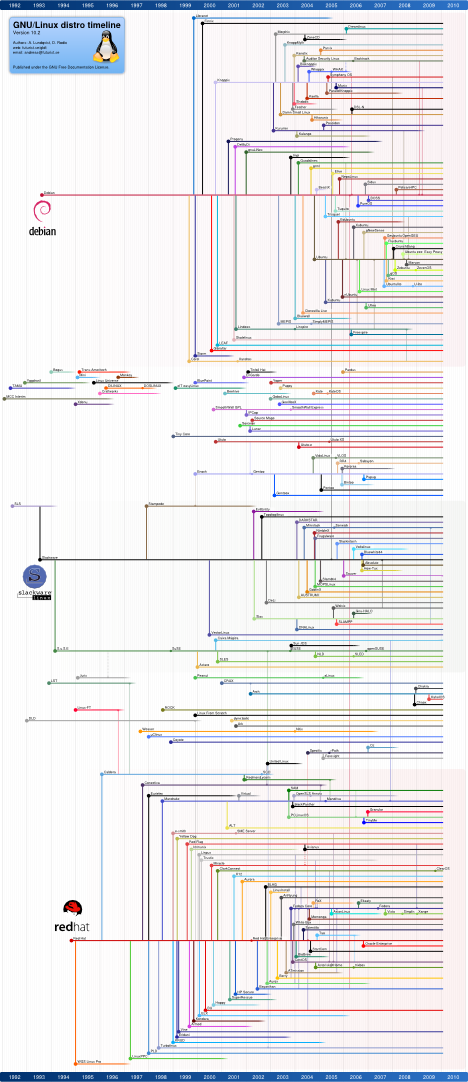

Since I tend to lag behind in my reading, I normally add interesting articles to my bookmarks and then proceed to read them when I find some time (by the way, if you find yourself in the same situation, you may be interested in an add-on for Firefox named Read It Later that helps you keep track of these). That's how I ended up reading back to back to recent articles published by Linux Magazine: The Five Distros That Changed Linux, by Steven Vaughan-Nichols, and The Three Giants of Linux, by Christopher Smart. The first one quickly discusses Slackware, Debian, Caldera, Red Hat and Ubuntu. The choices shouldn't be controversial at all. Sure, everyone has his/her favorite distro, but the ones picked by Vaughan-Nichols truly are the ones that made a difference in the Linux world. As for the second article, it's perhaps more interesting, for it only centers on the three distributions that represent the core from which most others came from (i.e., Slackware, Debian and Red Hat). These are the true "three giants of Linux", the innovators who managed to spawn a thousand children and whose work still benefits us all to this day. I especially recommend the GNU/Linux distro timeline put together by Lundqvist and Rodic included with the article (click on the screenshot to download the larger image):

{link to this story}

[Wed Mar 17 12:38:31 CET 2010]

Eric Bruno blogs in Dr. Dobb's Journal website about the e-books and muses about what he calls "the Digital Bookshelf":

The rest of the blog post also contains some other insightful comments. It's worth reading. {link to this story}...wouldn't it be neat if you could walk into a public library and have your Kindle, Reader, nook, or iPad recognize where you are, and then automatically make periodicals and other library-owned material available to peruse while you were there? It would be a "digital bookshelf", personalized for the library that you're in, but based on standards so that every public library in the nation that opts to participate could offer the same look and feel. Then, no matter which library you enter in the future, you'll have its full range of content at your fingertips to browse virtually while you were there, and borrow with a touch of the screen to read when you're back home or on the road... at least until the due date arrives :-)

[Fri Mar 12 11:16:29 CET 2010]

According to Computer World, hackers love to exploit PDF bugs. Citing a study by a Finnish security company, they explain that black hat hackers have pushed PDF vulnerabilities in Adobe Acrobat Reader to the top of the list, surpassing even Microsoft Office. I suppose this is a good reason to use alternative PDF readers, such as Evince on Linux and Preview on Apple. {link to this story}

[Tue Mar 9 11:59:05 CET 2010]

I truly like checking out the quotes of the week section on the kernel page published by Linux Weekly News. Some of them are funny, some other right on the money. For example, here is what somebody by the name of Valerie Aurora had to say about the topic of corporate policies and employee benefits:

It certainly is one of the problems of all those nice perks. You do get to keep your very bright employees happy and less willing to switch to another job but, on the other hand, they will also be more secluded from the outside world. As usual, there is no perfect solution to most important conundrums. It's always a combination of approaches that makes sense. {link to this story}The post-Google standard company perks —free food, on-site exercise classes, company shuttles— make it trivial to speak only to fellow employees in daily life. If you spend all day with your co-workers, socialize only with your co-workers, and then come home and eat dinner with —you guessed it— your co-worker, you might go several years without hearing the words, "Run Solaris on my desktop? Are you f-ing kidding me?"

[Fri Mar 5 10:55:03 CET 2010]

A good friend shared a link to a short piece titled I bought a CD, not a Licensing Agreement on Facebook. The piece is worth reading. It clearly shows how the music industry is trying to play the same game by two different sets of rules at the same time: while pretending that a CD bought at the store also entails accepting a non-written license agreement that goes well beyond the mere fact of owning a physical media, it also argues that the purchase is truly limited to the physical media when it suits them (e.g., when the media is scratched and the consumer demands a new copy of the content that was purchased). In this case, the industry is clearly being inconsistent. If they claim that I am not so much the owner of a physical media that I can use as I see fit but rather the signatory of a license agreement that only allows me to use the content itself, then they should be consistent and provide me with a new copy of the songs once the media has been scratched. Yet, they don't do this. Still, I disagree with the message implied in my friend's post that I should have a right to do whatever I want with the contents, including making thousands of copies and distribute them among whoever I want. There must be a sensible agreement that we can reach avoiding the two extremes. In this particular case, I'd say it makes sense to change the legislation to force the music industry to set up a system that allows people to register once they purchase any CD, so that they can access the music in digital format at a later stage should they need to, for example. Another possible solution would be to mail the old CD to the music label and, in exchange, they provide me with a way to download the contents of that CD from a website. {link to this story}