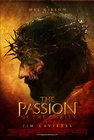

(The Passion of the Christ)

Duration: ??? minutes

Country: USA, 2004

Director: Mel Gibson

Cast: James Caviezel, Monica Bellucci,

Claudia Gerini, Maia Morgenstern,

Sergio Rubini

Language: Aramaic, Latin

If you are seriously considering to go see this movie, be warned this is one of those few occasions where the title truly defines what you will see: this is a movie about the passion of Christ, and not about his life. Passion as defined by its old Latin meaning (passio), and not by the cookie-cutter romantic comedies we have become too accustomed to:

A suffering or enduring of imposed or inflicted pain; any suffering or distress (as, a cardiac passion); specifically, the suffering of Christ between the time of the last supper and his death, esp. in the garden upon the cross. "The passions of this time." --Wyclif (Rom. viii. 18).

"Webster's Revised Unabridged Dictionary (1913)"

I say this because some (if not most) of the criticism launched against this movie is based precisely on this point. Leon Wieseltier, writing for the New Republic, called it Mel Gibson's Lethal Weapon, stressing that:

(...) The Passion of the Christ is intoxicated by blood, by its beauty and its sanctity. The bloodthirstiness of Gibson's film is startling, and quickly sickening. The fluid is everywhere. It drips, it runs, it spatters, it jumps. It trickles down the post at which Jesus is flagellated and down the cross upon which he is crucified, and the camera only reluctantly tears itself away from the scarlet scenery. The flagellation scene and the crucifixion scene are frenzies of blood. When Jesus is nailed to the wood, the drops of blood that spring from his wound are filmed in slow-motion, with a twisted tenderness. (Ecce slo-mo.) It all concludes in the shower of blood that issues from the corpse of Jesus when it is pierced by the Roman soldier's spear.

I beg to differ. Yes, the movie is violent. Yes, Christ's blood is omnipresent. And yes, the suffering of Jesus during, and prior to, his crucifixion is its main and only plot. However, there is little doubt in my mind that an actual Roman crucifixion had to look something like this. In other words, we face the ages old artistic dilemma: is it acceptable to portray reality in all its crudeness for the sake of allowing the viewers a direct experience? Or, on the contrary, should we resort to symbolism and metaphor in order to send the same message in a more subtle way? There are defenders and detractors of both positions. It has always been like that, and I do not think we will see it change any time soon. I must say though I find it quite interesting that the very same people who usually criticize Hollywood and mainstream media for their excesses of violence are now praising this movie for the very same reason. Yes, violence does serve a purpose in The Passion of the Christ, but then it also does in Apocalypse Now or Friday the 13th and we hear endless attacks from the moralistic right every single time they are screened. It certainly smacks of double standards, but no less than the double standards of those liberals who justify violence, no matter how bloody, as long as it is required by the plot and now object to the very same truculent displays in this movie. So, I suppose my attitude in this respect is the one I have always had: if violence annoys you, don't go see it.

One could question, of course, why Mel Gibson chose to tell us only about the passion of Christ, and not about his life, about the rest of his message. But then, of course, somebody else could also argue that it is precisely the crucifixion that became a central element to Christianity. It is surely not by chance that those who outlived Jesus chose the cross as their symbol. They could have chosen so many other elements from the Gospels and yet what became central to the early Christian Church (and has remained so all the way until our days) was precisely Jesus' death on the cross, his passion. But why? It could be due to the fact that I was raised in a Catholic country but perhaps what we need to understand is that blood, suffering, passion, violence, no matter how off putting may look to us, can also have a cathartic effect in our lifes. For some reason, this is something that appeared to be clear in ancient and medieval times and we have forgotten in our days. The old Greek tragedy is full of this sort of cathartic blood spilling, as are many other works of art from the Mediterranean cultures, and the same applies even to modern tragic artists I grew up with such as Lorca or Goya. And yet, for some reason, the simple-minded pacifism we have come to assume as the only moral choice in recent times totally abhors of this very idea that blood or violence may have any liberating effect whatsoever, although it does. Mind you, I am not a war monger myself, and am definitely not proposing any sort of death cult. However, I do dislike the simplistic non-violent approach to life as much as I detest its opposite. Life is always far more complex and contradictory than we want to make it and, thankfully, no single ideology or religion will manage to explain it all. We are thrown into existence against our own will, and all we can do is aspire to understand as much of it as we can while being fully aware that we will never manage to discover all the mysteries of life. That is precisely its beauty. That is the heart of our human struggle, the key to an endless pursuit that we feel compelled to embark on but that we know fully well will never take us to port. In this context, why should Christ's suffering be any less important than the rest of his life? Is it not the whole reason why he was born in the first place? Was he not sent to us, in the first place, to die for our sins? Is there nothing to admire in the fact that someone could willingly accept such sacrifice in the name of love, love for Humanity as a whole and not for this or that single person? Again, I beg to differ. I can certainly see the point of those who criticize Mel Gibson's movie as a blood feast, and fully understand their disgust when they realized so much of the life of Christ was left out of it. I just do not see that way. To me, it is just like those who oppose other movies because they show sex or poverty. Well, sorry. Welcome to life. Welcome to a world of joy, tears, blood, happiness, violence, sex, love, poverty, comfort, laughter, hatred and death. Take it or leave it but, please, do not falsify it, do not limit it, do not simply cut out all the parts you feel uncomfortable with. Life is too beautiful to do that.

In this sense, I could not disagree more with William Safire's opinion expressed in the pages of The New Tork Times:

Again, it could be due to my upbringing in a Catholic culture. While my parents raised me in a secular and even agnostic environment, the truth remains that Spain is still a very Catholic country at least when it comes to its overall cultural background. As someone born in Seville, capital of perhaps the most exalted imagery of the Passion of the Christ in the whole country, I can hardly feel shocked by the suffering Mel Gibson shows on the screen.Mel Gibson's movie about the torture and agony of the final hours of Jesus is the bloodiest, most brutal example of sustained sadism ever presented on the screen.

(...)

What are the dramatic purposes of this depiction of cruelty and pain? First, shock; the audience I sat in gasped at the first tearing of flesh. Next, pity at the sight of prolonged suffering. And finally, outrage: who was responsible for this cruel humiliation? What villain deserves to be punished?

But Safire's last question remains unanswered: what villain deserves to be punished? He thinks he knows Mel Gibson's answer, which takes us into yet another controversial aspect of the movie: its alledged antisemitism.

This is the essence of the medieval "passion play," preserved in pre-Hitler Germany at Oberammergau, a source of the hatred of all Jews as "Christ killers."

Much of the hatred is based on a line in the Gospel of St. Matthew, after the Roman governor washes his hands of responsibility for ordering the death of Jesus, when the crowd cries, "His blood be on us, and on our children."

Though unreported in the Gospels of Mark, Luke or John, that line in Matthew —embraced with furious glee by anti-Semites through the ages— is right there in the New Testament. Gibson and his screenwriter didn't make it up, nor did they misrepresent the apostle's account of the Roman governor's queasiness at the injustice.

But biblical times are not these times. This inflammatory line in Matthew —and the millenniums of persecution, scapegoating and ultimately mass murder that flowed partly from its malign repetition— was finally addressed by the Catholic Church in the decades after the defeat of Nazism.

In 1965's historic Second Vatican Council, during the papacy of Paul VI, the church decided that while some Jewish leaders and their followers had pressed for the death of Jesus, "still, what happened in his passion cannot be charged against all Jews, without distinction, then alive, nor against the Jews of today."

Well, we finally arrive at the core of the issue, the true reason why so many people are having problems with this movie: its orthodox interpretation of the Gospels, its literal and faithful acceptance of what is written in the Scriptures and, by extension, its traditionalist approach to the ages-old debate on whether the description of the Passion of Christ written by Matthew is or is not antisemitic. Yes, the violence is honestly repulsive to many people. Yes, Gibson seems to rejoice in the suffering of a fellow human with the argument that he simply sacrificed his own life for love of us, sinners. However, the real problem most people have with this movie is not all that. The real bone they pick is Mel Gibson's traditionalist approach to the Gospels. Did I find The Passion of the Christ to be antisemitic? No. Leo Wieselter, writing for The New Republic, holds a different view, but I simply cannot see how anybody can go into the viewing room been neutral on the issue and come out hating the Jews. Could it be perhaps that I am agnostic after all, and do not feel as if the Jews committed any crime against my Messiah? I doubt it. I went to see the film with three hundred members of a Christian church, and I did not hear any antisemitic comment coming from them. They certainly did not feel any sort of hatred towards the Jews after watching Mel Gibson's account of their Lord's Passion. Now, can I see how Gibson does not do anything to counter the more traditional interpretation of the Passion, according to which the Jews are to blame for Christ's crucifixion? Yes, I certainly do. In other words, no neutral person will come out and antisemitic, but any antisemitic viewer will probably come out from the viewing room with his own prejudices reinforced. Is that troublesome? I am not sure. You be the judge. I think I would rather side with Michael Medved (a practicing Jew, incidentally) when he states that:

The organized Jewish community and its allies in interfaith dialogue may not welcome Passion, but overreaction will provoke far more anti-Semitism than the movie itself.

Gibson financed the film on his own precisely due to his determination to realize his own traditionalist Catholic vision of the Gospel story without compromise to the sensitivities of profit-oriented accountants or other religious perspectives. Jewish leaders feel wounded that he never consulted them on the script or historic details, but he also left out Protestant and Eastern Orthodox traditions.

(...)

By agonizing so publicly about the purportedly anti-Semitic elements in the story, the Anti-Defamation League makes it vastly more likely that moviegoers will connect the corrupt first-century figures with today's Jewish leaders.

(...)

Many Jews understand that the canonized accounts were created at a time when early Christians had begun to despair of converting Jews, and instead focused their attention on proselytizing Romans. Hence, orthodox Jews come out looking very bad, while Pilate and other Roman authorities receive less blame.

(...)

We may not welcome the stories told by Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John, but Christians have cherished the record for 2,000 years. The fact that anti-Semites have used these accounts as the inspiration for their depredations may prove that those stories can be dangerous, but it doesn't prove them untrue. Jewish organizations must not attempt to take responsibility for deciding what Christians can and cannot believe. If they do, they force a choice between faithfulness to scripture and amiable relations with Jews.

(...)

Do we feel comfortable when some evangelical observers insist that they know more about the real symbolism of our Jewish rituals - emphasizing their supposed anticipation of Jesus the Messiah - than we do?

(...)

From a Jewish perspective, the most unfortunate aspect of the dispute involves the renewed focus on Christian scripture when most Americans —including most Jews— remain ignorant of the most fundamental Jewish teachings —other than a general sense that Jews respect Moses and refuse to accept Jesus as Messiah. The interest of Jewish continuity and vitality can hardly be served by a battle over a movie that will succeed with the public regardless of our discomfort. Rather than wasting energy and good will to discredit an artful and ambitious film, we would do more for the cause of Judaism to emphasize the positive and productive aspects of our own sacred tradition.

From my agnostic perspective, what I saw on the screen were a group of perfectly fallible men (just like you or me) pushing Pilate to sentence Jesus to death out of political ambition as well as the pragmatic interest to keep a fragile peace. In a time when the Romans had put a bloody end to several Jewish uprisings, it is not so difficult to understand how both the Pilate the governor and the Sanhedrin might have an interest in keeping the fragile equilibrium they had reached, instead of risking it all to follow a semi-revolutionary figure who claimed to be the new Messiah (incidentally, one of many around that time who claimed to be the Savior sent by God himself to save the Jewish people from submission to the temporal powers). Perhaps the problem is not so much that Mel Gibson's movie has some antisemitic connotations as the fact that the Christian Gospels themselves take that approach, at least the one written by Matthew. As Medved points out, that is quite dangerous, but it is something that can only be avoided in two ways: either allowing for an interpretation of the Scriptures in view of the historical context, or refusing to believe that they were inspired by God at all.

In any case, at a time where we see so many soulless productions that are ready made according to well proven formulas to assure profitability, I believe Mel Gibson's personal gamble is a breath of fresh air, no matter what one thinks of his ideas and religious beliefs. Besides, it was about time that we could see a movie where Christ's suffering is portrayed with some degree of realism, instead of the soft treatment that the topic has traditionally been given on the screen. Call me stupid, but I liked the movie, even though I deeply dislike the director's ideas.

Entertaiment factor:6/10

Artistic factor:7/10